Michelangelo Buonarroti's remarkable accomplishments include sculpting the impeccable 17-foot statue of David from an imperfect block of marble, enduring physical exertion on scaffolding to illustrate the divine narrative across the Sistine Chapel's ceiling, and later pioneering architectural innovations, such as the Laurentian Library and the New Sacristy, that transformed Florence and Rome. Michelangelo Buonarroti was far more than an artist; he represented the indomitable essence of the Renaissance. His challenging early experiences, affiliations with the Medici family, rivalry with Leonardo da Vinci, and profound influence on modern art collectively reshape traditional conceptions of genius.

Who Was Michelangelo?

.jpg_00.jpeg)

Michelangelo Buonarroti, one of the most esteemed figures of the Renaissance period, was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, a village near Florence, Italy. He regarded Florence as his lifelong home.

Demonstrating exceptional artistic aptitude from an early age, he apprenticed under the distinguished painter Domenico Ghirlandaio in Florence, where he refined his expertise in painting and drawing.

Michelangelo's artistic practice and oeuvre was profoundly shaped by the humanist principles of the Renaissance, which underscored the meticulous study of the human figure, form and anatomy to attain realism and emotional profundity in his compositions. He actively participated in the intellectual discourse of the Platonic Academy, which enriched his philosophical perspective on artistic creation.

His multifaceted genius extended across sculpture, painting, architecture including the New Sacristy for Giuliano de’ Medici, and poetry, establishing him as a paradigmatic polymath of the epoch.

His enduring masterpieces continue to evoke admiration and scholarly examination even after several centuries.

Early Life and Education of Michelangelo

Michelangelo's early life in Florence was characterized by his deep immersion in the city's dynamic artistic milieu, facilitated by the patronage of the Medici family, notably Lorenzo de' Medici, who early recognized the young artist's exceptional talent.

Born in 1475 near Caprese, Michelangelo was relocated to Florence in childhood, where his family apprenticed him at the age of 13 to the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio for formal instruction in painting. In this environment, he refined his proficiency in preparatory drawings through red chalk and black chalk techniques, establishing a solid foundation for his subsequent expertise in three-dimensional models, sculpture and fresco painting.

He later transitioned to the Medici gardens, where he studied ancient sculptures under the guidance of Bertoldo di Giovanni, thereby internalizing classical influences that profoundly informed his mastery of anatomical accuracy.

- Among his initial significant works was the Battle of the Centaurs relief, which demonstrated his emerging sculptural acumen.

- His chalk studies, as chronicled in Giorgio Vasari's and Ascanio Condivi's Lives of the Artists (1550), attest to the nascent brilliance of a talent nurtured within Lorenzo's humanist intellectual circle.

This formative period, bolstered by the Medici family's resources, positioned Michelangelo for groundbreaking contributions to the Renaissance, as manifested in his enduring masterpieces.

What Were Michelangelo's Major Artistic Achievements?

Michelangelo's principal artistic accomplishments represent the zenith of Renaissance ingenuity, exemplifying his exceptional proficiency in sculpture and painting, which profoundly transformed the domain of artistic expression.

The renowned marble statue of David, meticulously carved from a single block of marble, embodies the ideal of human potential and the ethos of Florentine republicanism; standing over 17 feet tall, it resides prominently in Florence.

The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, commissioned by Pope Julius II, is adorned with monumental frescoes depicting scenes from the Book of Genesis, including the iconic Creation of Adam, distinguished by its innovative incorporation of heroic nudes, ignudi figures, and illusionistic compartments to evoke divine energy and human vitality.

Complementing this masterpiece, commissioned by Pope Paul III, the Last Judgment on the chapel's altar wall, later modified by Daniele da Volterra, presents a dramatic portrayal of salvation and damnation.

His earlier sculptures, such as the Pietà sculpture and the late Rondanini Pietà, convey profound emotional depth through the Madonna Child's sorrow over the Child, while works like the Bacchus statue and the Holy Family tondos illustrate his pioneering approach to form and illusionistic spatial arrangements, influencing successive generations of artists with their anatomical precision and expressive potency.

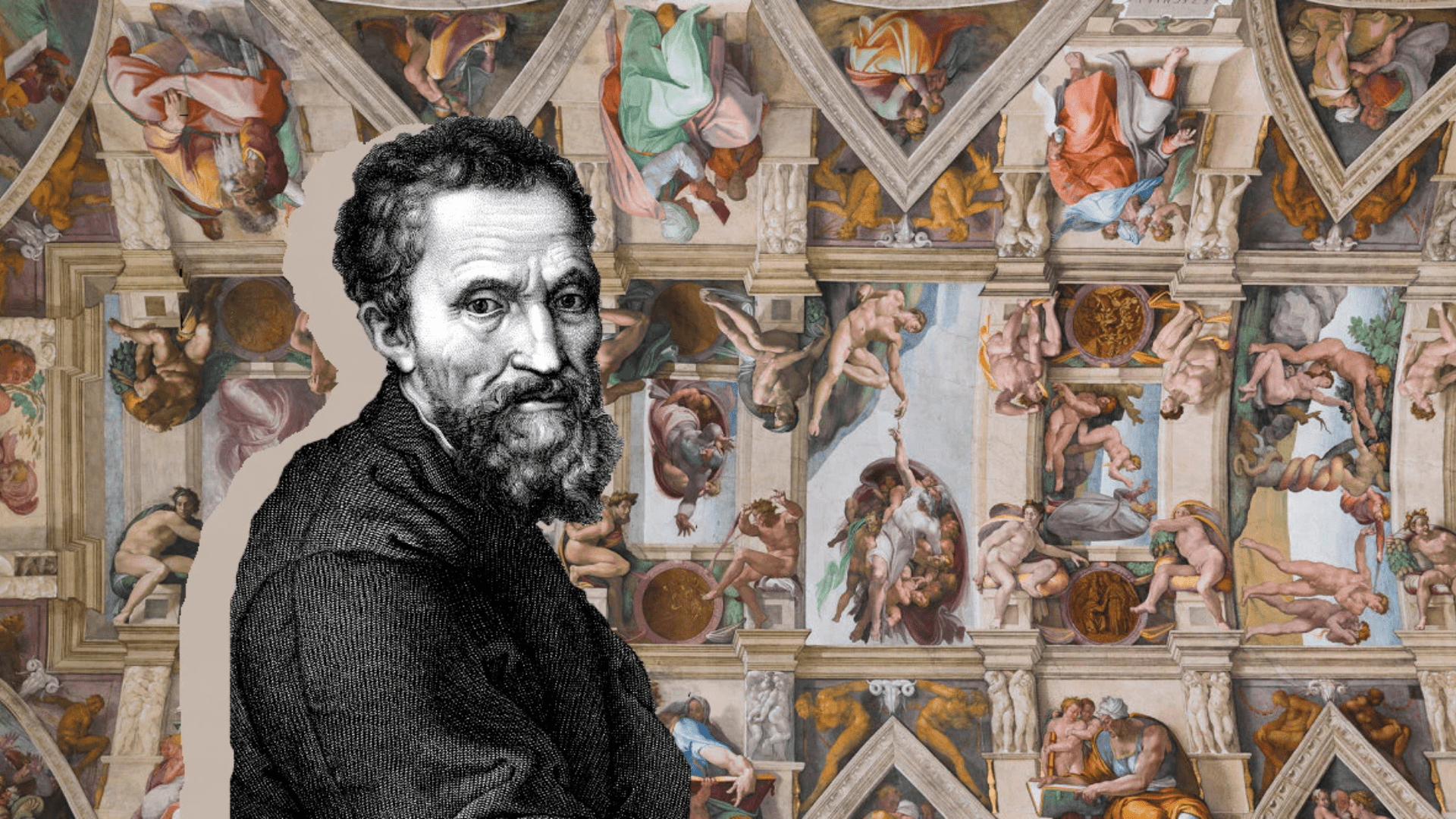

The Sistine Chapel Ceiling: Creation and Significance

.jpg_01.jpeg)

The Sistine Chapel ceiling, executed between 1508 and 1512 under the patronage of Pope Julius II, stands as Michelangelo's most ambitious fresco endeavor within the Vatican City.

Commissioned during the height of the Renaissance, it converted the Vatican's sacred interior into a profound visual representation of theological creation. Although Michelangelo, renowned primarily as a sculptor, initially resisted the assignment, the pope's resolute directive ensured its realization, thereby establishing one of the landmark papal commissions that seamlessly integrated artistic mastery with doctrinal imperatives.

The project's execution presented formidable challenges: Michelangelo labored on his back atop extensive scaffolding for four years, which exacted a significant physical toll.

Nevertheless, he introduced innovative methods, including the use of full-scale cartoons to facilitate accurate transfers onto the fresco surface.

To attain unparalleled anatomical precision, he conducted studies of dissected corpses and human cadavers at local hospitals, as documented in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists (1550), with historical records from the Accademia di San Luca indicating examinations of more than 30 bodies.

- Theological significance: The ceiling features nine scenes from the Book of Genesis, emblematic of divine order and human capability, thereby bolstering papal authority amid the religious turbulence of the period.

- Renaissance innovation: This masterpiece advanced fresco techniques to new heights, profoundly influencing contemporaries such as Raphael and exemplifying the humanistic renaissance through its sophisticated integration of perspective and anatomical detail.

David: The Iconic Sculpture and Its Impact

Michelangelo's David, unveiled in 1504 in Florence, Italy, stands as a monumental marble statue that exemplifies the Renaissance ideal of the human form, characterized by its intricate depiction of the muscular body and anatomy and heroic poise.

Commissioned in 1501 from a large, imperfect block of marble previously abandoned by other sculptors, the statue was completed over three years, demonstrating Michelangelo's exceptional skill in converting flawed material into an enduring emblem of victory.

Although not directly associated with the Battle of Cascina—a 1364 conflict in which Florentine forces triumphed over Milanese troops amid foggy conditions—the sculpture captures the essence of underdog determination.

David's sling and resolute gaze symbolize civic resistance against formidable adversaries, such as the Medici family or external invaders.

The statue's public reception was profoundly enthusiastic, with audiences captivated by its grandeur and lifelike quality; it was subsequently relocated from the cathedral to the piazza of the Palazzo Vecchio to represent Florence's republican ethos.

This heroic nude transformed the representation of human anatomy in art, employing the contrapposto stance and meticulous vascular details that profoundly influenced subsequent generations of artists.

As documented in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists (1550), the work is lauded for its remarkable vitality and realism.

- Symbolic dimensions: The idealized proportions of David emphasize youth and vigor, reinforcing Florence's stature as a leading center of culture and innovation.

- Enduring legacy: The statue has inspired neoclassical sculptures and contemporary reproductions, attracting more than 10 million visitors annually to the Accademia Gallery, according to data from the Italian Ministry of Culture.

What Was Michelangelo's Role in the Renaissance?

Michelangelo Buonarroti occupied a central position in the Renaissance era, serving as a vital link between the artistic legacies of Florence and Rome, and promoting humanist principles that extended their influence throughout the Roman Catholic Church and into broader society.

Originating from the birthplace of the Renaissance in Florence, Italy, he subsequently relocated to Rome, where he undertook monumental commissions from the papacy in Vatican City, notably contributing to the construction of Saint Peter’s Basilica, succeeding Antonio da Sangallo—a project emblematic of the period’s integration of artistic expression, religious devotion, and classical antiquity.

Born Michelangelo Buonarroti on March 6, 1475, his association with the Medici family in Florence resulted in architectural designs such as the Laurentian Library and the New Sacristy, which introduced groundbreaking innovations in spatial organization and profoundly shaped subsequent developments in artistic composition.

Michelangelo’s participation in the Platonic Academy further deepened his engagement with philosophical inquiry, thereby imbuing his creations with profound intellectual resonance.

Renowned as a sculptor, painter, and architect, he transformed the perception of the artist from mere artisan to intellectual visionary, encapsulating the Renaissance ethos of ingenuity, anatomical accuracy, and emotive magnificence that enduringly transformed Western art and culture.

Michelangelo's Relationship with the Medici Family

.jpg_10.jpeg)

Michelangelo's profound connections with the Medici family, which originated during his youth in Florence under the patronage of Lorenzo de' Medici, significantly influenced his professional trajectory and artistic achievements.

Following his apprenticeship with Domenico Ghirlandaio, from an early stage, he profited from Lorenzo's guidance, which placed him in a supportive environment reminiscent of family life, where he refined his abilities among the classical sculptures in the Medici gardens. This immersion further encompassed the intellectual vitality of the Platonic Academy, where engagements with Neoplatonism alongside scholars such as Marsilio Ficino broadened his intellectual horizons, integrating artistic practice with philosophical inquiry.

- The Laurentian Library, designed to house the family's collections, exemplified his architectural ingenuity through its striking vestibule and harmonious staircases.

- The New Sacristy, a mausoleum dedicated to Giuliano de’ Medici, manifested his personal allegiances via poignant sculptures that symbolized the eternal spirit.

These associations, as recorded in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists (1550), emphasized the familial and intellectual collaborations that elevated his stature in the Renaissance, thereby guaranteeing sustained support from the Medici family.

What Were Michelangelo's Architectural Contributions?

Michelangelo's architectural contributions during the Renaissance represented a transformative evolution in design principles, seamlessly integrating classical Roman elements with pioneering spatial innovations that profoundly influenced the Baroque period and subsequent architectural developments.

In Rome, Italy, he assumed responsibility for the design of Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican following the death of Antonio da Sangallo, reenvisioning the dome through meticulous mathematical precision and monumental scale to embody the symbolism of eternal faith.

Earlier, in Florence, his designs for the Laurentian Library and New Sacristy pioneered Mannerist characteristics, including illusionistic spatial divisions and fluid, dynamic staircases that subverted conventional notions of symmetry. Michelangelo executed these ambitious visions utilizing three-dimensional models and intricate technical drawings, thereby treating structural elements as extensions of sculptural form. His endeavors on these projects not only advanced the artistic prestige of architecture but also fused it with his inherent sculptural philosophy, yielding environments that inspire profound emotional resonance and a sense of dynamic vitality.

Consequently, these works solidified his enduring legacy as a polymath of the Renaissance, whose architectural masterpieces continue to be revered and analyzed as exemplars of global significance.

The Design of St. Peter's Basilica

Michelangelo's design for Saint Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, undertaken in 1546 at the direction of Pope Paul III, elevated the project to a profound embodiment of Renaissance architectural principles.

At the age of 71, he assumed oversight of a disorganized construction site in Rome, Italy, hampered by prolonged delays and divergent concepts from earlier architects such as Donato Bramante and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger.

His redesign refined the basilica's structure, adopting a centralized Greek cross plan that underscored the unity of the Church amid the Counter-Reformation.

Key structural advancements featured the renowned double-shell dome, inspired by ancient Roman techniques, which reached a height of 136 meters and exemplified his expertise in proportion and illumination.

- Integrated Corinthian pilasters established a cohesive rhythm across the facade.

- Innovative ribbed vaults effectively distributed structural loads, mitigating the risk of collapse.

- Papal commissions affirmed the basilica's significance as a cornerstone of Roman Catholic tradition, harmonizing classical antiquity with Christian iconography.

As chronicled in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), this accomplishment in Michelangelo's later years embodied his conception of divine geometry. A 2019 analysis by the Vatican Museums elucidates how these features bolstered the basilica's spiritual preeminence, attracting millions of visitors to its hallowed precincts each year.

What Challenges Did Michelangelo Face?

.jpg_11.jpeg)

Throughout his distinguished career, Michelangelo encountered a series of formidable challenges that both tested his fortitude and profoundly influenced his artistic development, encompassing intense rivalries, exacting patrons, and significant physical adversities.

His renowned rivalry with Leonardo da Vinci in Florence exemplified divergent artistic philosophies, engendering public discourse and personal discord. Papal commissions from figures such as Julius II and Paul III frequently imposed rigorous deadlines and political exigencies, as exemplified by the Sistine Chapel undertaking, during which he grappled with scaffolding difficulties and considerable physical exertion.

Subsequently, The Last Judgment provoked controversy and censorship, prompting Daniele da Volterra to modify certain figures posthumously.

Biographers Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi chronicled his travails, including meticulous anatomical studies derived from dissected cadavers and the arduous preparation of full-scale preparatory cartoons.

Notwithstanding these impediments—encompassing financial difficulties, repeated relocations between Florence and Rome, and the psychological burden of incomplete projects such as the Rondanini Pietà—Michelangelo's steadfast determination produced enduring masterpieces, thereby illuminating the arduous yet ultimately victorious trajectory of a Renaissance luminary whose trials enhanced his enduring contributions to the annals of art history.

Michelangelo's Rivalry with Leonardo da Vinci

Michelangelo's rivalry with Leonardo da Vinci, which originated in Florence, Italy, circa 1504, arose from competing commissions and fundamentally divergent artistic methodologies.

This rivalry reached its zenith when the city's council commissioned parallel fresco projects for the Sala del Gran Consiglio in the Palazzo Vecchio: the Battle of Anghiari to the elder artist, Leonardo, and the Battle of Cascina to the younger Michelangelo, a sculptor transitioning to painting. Their stylistic differences were pronounced—Leonardo's technique employed sfumato, characterized by fluid, atmospheric effects that softened contours and conveyed emotion through nuanced tonal gradations, in contrast to Michelangelo's focus on anatomical exactitude and vigorous, muscular compositions evocative of classical sculpture. These distinctions are documented in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550).

Subtle mutual influences also surfaced; scholarly examinations indicate that Leonardo's engagement with anatomy intensified, while Michelangelo's preparatory cartoons informed more ambitious compositions in endeavors such as the Sistine Chapel ceiling depicting scenes from the Book of Genesis and Book Genesis.

As art historian John Shearman elucidates in The Early Italian Engravings (1973), this competition advanced Renaissance innovation by compelling artists to integrate intellectual depth with corporeal dynamism, thereby enhancing the enduring international prominence of Florentine art.

What Is Michelangelo's Legacy?

Michelangelo Buonarroti's enduring legacy stands as a foundational pillar of Western art, exemplifying the Renaissance's pinnacle of innovation, emotional profundity, and technical mastery, the effects of which continue to reverberate in contemporary culture.

His sculptural works, including the renowned Pietà sculpture, the iconic David statue, the Bacchus statue, and the incomplete Rondanini Pietà, poignantly evoke universal themes of human anguish and divine transcendence. His paintings, such as the Holy Family featuring the Madonna Child, further exemplify his versatility. Similarly, the monumental frescoes of The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel demonstrate his unparalleled command of compositional structure and narrative storytelling within the hallowed precincts of the Roman Catholic Church.

Documented in the biographies by Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo's life has served as the inspiration for numerous subsequent accounts, underscoring his unyielding quest for perfection through rigorous preparatory drawings and detailed anatomical investigations. His influence transcends the visual arts, permeating literature and philosophy, where he is often portrayed as a quasi-divine figure embodying the creative spirit.

In the present day, Michelangelo's masterpieces, housed in Florence Italy, Rome Italy, and the Vatican City, attract millions of visitors annually, serving as enduring emblems of humanism's victory over adversity. This rich and multifaceted heritage not only safeguarded classical principles but also advanced artistic expression toward innovative explorations of individualism and spirituality, cementing Michelangelo's reputation as an archetype of genius throughout history.

How Did Michelangelo Influence Modern Art?

Michelangelo's profound influence on modern art is evident in the enduring admiration for his heroic nudes and depictions of muscular forms, which have inspired artistic movements ranging from Mannerism to Abstract Expressionism.

His stylistic legacies, characterized by intense emotional expression and meticulous anatomical precision, profoundly shaped Mannerist artists such as Pontormo, who employed elongated forms to amplify dramatic effect, thereby echoing the Renaissance master's tormented grandeur. In the transition to the 20th century, sculptors like Henry Moore drew upon these principles, adapting muscular torsos into semi-abstract bronzes that conveyed universal human struggles, as exemplified in Moore's 1940s Shelter Sketches, which were informed by themes of wartime resilience.

- Preparatory drawings in red chalk, such as those for the Battle of Cascina and the Sistine Chapel figures housed in the British Museum, inspired modern draftsmen through their fluid contour lines that reveal underlying tension.

- Black chalk studies, featured in a 2018 exhibition at the Uffizi Gallery, influenced Abstract Expressionists like Willem de Kooning, who incorporated the raw physicality evident in these works into their gestural paintings.

A 2020 study published in the Journal of Art History traces this artistic lineage, highlighting how regulations governing classical anatomy in art education have sustained Michelangelo's technical inspirations in contemporary installations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Michelangelo and when was he born?

Michelangelo Buonarroti was a renowned Italian Renaissance artist, sculptor, painter, architect, and poet, born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy. He apprenticed with Domenico Ghirlandaio and was influenced by contemporaries like Leonardo da Vinci. He is celebrated for his masterpieces like the Holy Family featuring the Madonna Child, the David statue, and the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Who was Michelangelo and what were his most famous sculptures?

Michelangelo was one of the greatest artists of the Italian Renaissance, famous for sculptures such as the Pietà sculpture, the David statue, the Moses, the Bacchus statue, and his late work the Rondanini Pietà. His works exemplify the humanist ideals of the era, showcasing incredible anatomical detail and emotional depth.

Who was Michelangelo and what is his connection to the Sistine Chapel?

Michelangelo was a pivotal figure in the Renaissance, commissioned by Pope Julius II to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel between 1508 and 1512. Later, he was commissioned by Pope Paul III to paint the Last Judgment on the altar wall between 1536 and 1541 for the Roman Catholic Church. This monumental fresco includes scenes from the Book of Genesis and the Book Genesis, like The Creation of Adam, and the Last Judgment is considered one of the greatest artistic achievements in history. Notably, Daniele da Volterra was tasked with covering the nude figures in the Last Judgment after Michelangelo's death.

Who was Michelangelo and how did he contribute to architecture?

Michelangelo was a multifaceted genius of the Renaissance who also excelled in architecture, designing the Laurentian Library and the New Sacristy for the Roman Catholic Church, and contributing to Saint Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City after Antonio da Sangallo's death. His architectural style blended classical elements with innovative designs, influencing Baroque architecture.

Who was Michelangelo and what was his relationship with the Medici family?

Michelangelo was an Italian artist whose career was profoundly shaped by the Medici family, particularly Lorenzo de Medici; he lived in their palace in Florence Italy as a young man, participated in the Platonic Academy, and later received patronage from them. This support allowed him to create works like the Medici Chapel tombs in the New Sacristy for Giuliano de’ Medici and Lorenzo de Medici, reflecting his deep ties to Florentine patronage.

Who was Michelangelo and what is his lasting legacy?

Michelangelo was a towering figure of the High Renaissance whose innovative techniques in sculpture, painting, and poetry influenced generations of artists. His legacy endures through icons like the David and Sistine Chapel, symbolizing human potential and artistic excellence that continues to inspire today.

Who Is Henri Matisse ?

What Was Jean Michel Basquiat Famous Artworks ?